For many captains, crew and sea travelers, what is today the North Carolina coastal resort vacation islands known as the Outer Banks means treacherous ocean currents and shipwrecks.

Shipwreck of the Brig Washington

It is very much a part of local history and lore on these barrier islands. An untold number of ill-fated boats and ships as well as many of the courageous crews who manned them have gone down beneath the waves.

The Tiger, an British ship of Sir Richard Grenville's expedition, was the first known unfortunate vessel, wrecking here in June 1585. The latest may be in tomorrow's headlines. Why have so many boats and ships been lost, even after the deadly dangers of the "Graveyard of the Atlantic" became widely known? Unfortunately, avoiding these navigational hazards is much more difficult than simply recognizing them. In days passed, it was the wooden sailing ship carrying trade goods and passengers that kept the nation's commerce afloat. To follow the trade routes along the coast, thousands of these ships had to round not only North Carolina's barrier islands, which are located as much as 30 miles off the mainland, but also the infamous Diamond Shoals, a treacherous, always-shifting series of shallow, underwater sandbars extending over ten miles out from Cape Hatteras.

Navigating Diamond Shoals is not the only challenge, there are several other complicating factors. First, there are two strong ocean currents that collide off Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, the cold-water Labrador Current from the north and the warm Gulf Stream from the south, converge just offshore from the cape. To make use of of these currents, vessels must come very near the Outer Banks. Usually using this course wouldn't lead to trouble, but the winds and storms common to the region can sometimes make it a dangerous practice. Hurricanes and northeasters overpower ships with strong winds and heavy seas or force them ashore to be battered apart by the crashing breakers. Since the low islands offer no natural landmarks, ships caught in storms often grounded before spying shore and recognizing their misfortune. When combined, these natural factors form a navigational horror story that's feared as much as any worldwide.

Pirates and privateers, the Civil War, and German submarine attacks have added to the large toll nature has claimed. The grim total of boats and ships lost near Cape Hatteras is estimated at over a thousand. While these ships now rest in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, their legacy endures. Seamen marooned on the islands often chose to remain, establishing families and a heritage, which remains to this day. A lot of island inhabitants made a significant part of their living scavenging cargoes (a practice called "wrecking") and more than a few of local buildings were built entirely or in part from wreck timbers.

Because of the frequent storms and many other navigational hazards resulting in great loss of vessels, the U.S. Lighthouse Service and U.S. Lifesaving Service which became the U.S. Coast Guard have kept a steady watch for approximately 200 years. Though most of the area wrecks have decayed and are lost to the ocean forever, divers have access to a diverse assortment of sunken vessels offshore. Many shipwrecks also lie hidden under the sand dunes and can be exposed by storms. After a little time they're again covered when beach sands shift.

Laura Barnes

The Laura Barnes is representative of the many wooden sailing ships that were lost on the Outer Banks. The four-masted schooner came ashore in dense fog on the night of June 1, 1921, and the crew was rescued by Coast Guardsmen from nearby Bodie Island Station.

Her remains have since been relocated a mile south of their original location to Coquina Beach (across from the Bodie Island Lighthouse) for public viewing. An exhibit provides additional information about the wreck. Directions: 4.7 miles south of Whalebone Junction, or 3.3 miles north of Oregon Inlet campground. Drive to Coquina Beach parking area. Walk over to the beach.

Lois Joyce 1981

One of the Outer Banks' most recent shipwrecks, the Lois Joyce was a 100-foot commercial fishing trawler lost in 1981 while attempting to enter Oregon Inlet during a December storm. Though the crew was rescued by Coast Guard helicopter, the $1,000,000 vessel was a total loss. The wreck is located on the northern, ocean-side hook at the mouth of Oregon Inlet, and is best viewed at low tide. It is accessible by four-wheel drive vehicles only.

Oriental 1862

A Federal transport during the Civil War, the steamship Oriental has been grounded in her present position since 1862. Local rumor has it that some of the area's largest fish make their home in the Oriental's rusty remains. You can sometimes see the exposed boiler and smokestack in the ocean surf off Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. Directions: Seven miles south of Oregon Inlet campground, or 30 miles north of Buxton. Park at turnout for Pea Island Comfort Station. Board walk leads to wooden remains which are occassionaly exposed on the beach nearby. A wooden bow is located on the beach 1 mile north.

Margaret A. Spencer (wreck date unknown)

Located 14 miles south of Oregon Inlet Campground and 25-miles north of Buxton. Park on road strip 1 mile north of Rodanthe, cross the dunes, then walk 1.8 miles north on the beach. The wooden shipwreck is lying open, keel up, at the surf line.

LST 1948

Drive to the Rodanthe Fishing Pier, 15 miles south of Oregon Inlet campground, or 25 miles north of Buxton. Look north from Ramp 10 near the pier for the steel wreck in the water.

G.A. Kohler 1933

Driven ashore by a hurricane in 1933, the huge, four-masted schooner G.A. Kohler remained stranded on the beach for ten years.

Shipwreck of the schooner G.A. Kohler

The ship was subsequently burned during World War II for her iron fittings, but the charred remnants of the Kohler remain. Often obscured by shifting sand, the wreck is located off Ramp #14.

Altoona 1878

Drive to the parking lot near Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Walk over the ramp to the beach, then south along the beach approx. 1/2 miles.

On Ocracoke Island there are unidentified wooden remains near the first visitor parking turnout.

Courtesy: National Park Service - Cape Hatteras National Seashore

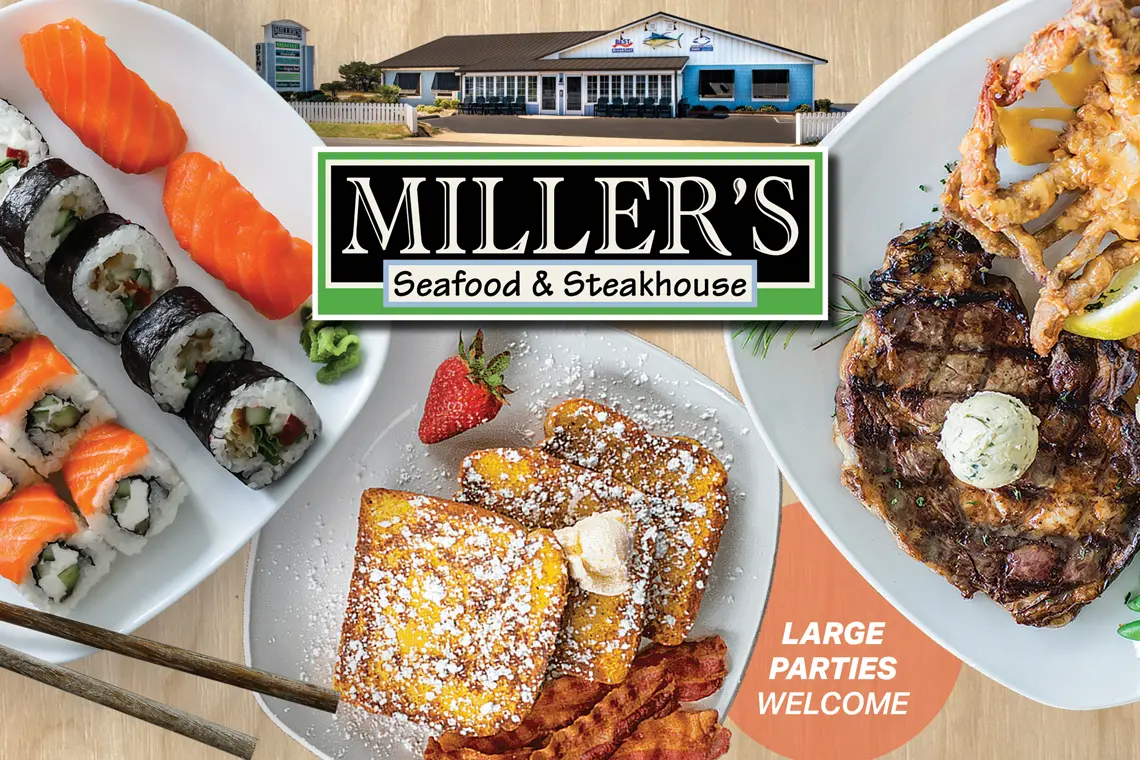

Miller's Seafood & Steakhouse has been a favorite among locals and visitors for more forty years. Offering delicious southern cuisine for both breakfast and dinner in a casual family atmosphere infused with coastal flair, it's no wonder this...

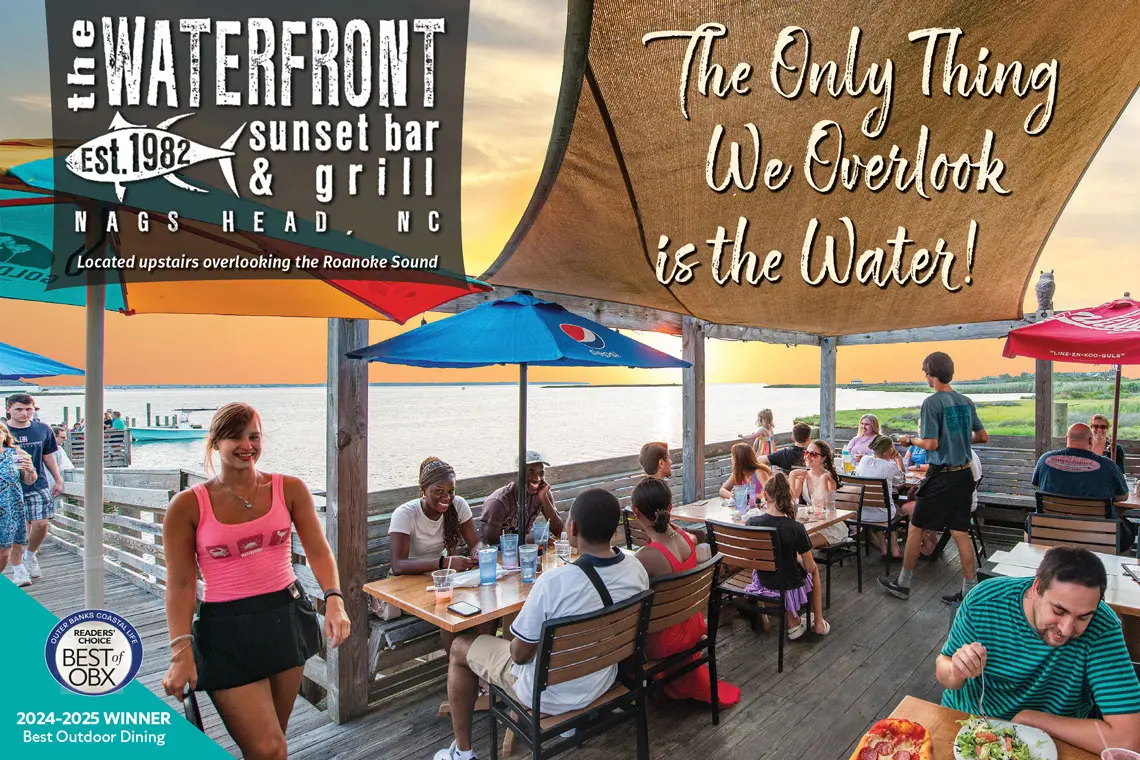

MILLER’S OFFERS ONE OF THE FEW TRULY WATERFRONT DINING EXPERIENCES ON THE OUTER BANKS. Enjoy casual dining in our downstairs family-friendly seafood restaurant, or our signature drinks and grill menu in our upstairs deck bar while watching...

Since 1968, our family owned and operated company has offered families just like yours a wide selection of Outer Banks vacation rentals in beach communities and towns of Duck, Southern Shores, Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills, Nags Head and South Nags...